How to write Chinese [1/n]

This post is long overdue. By now, I must have explained how to write Chinese characters to several of my friends. Story of my life: postpone writing a document/post until after realizing that the time spent explaining the same thing over and over roughly equals 10x the time it would take to write the document.

I’d like to make this post the first in a series about the oddities of living in China. That is, about the oddities that I still notice after having lived here for 10 months.

Part 1: How to write Chinese

If you’re like me you’ve often wondered how the Chinese are able to use a keyboard with 5000+ keys. Allow me to clear it up: they don’t. Chinese characters (and characters of other strange scripts) are written using a piece of software called an Input Method Editor or IME. The IME converts keystrokes (from a normal* keyboard) into the actual character.

To type Chinese, the user just enters the Latin characters corresponding to each character’s pinyin representation. Pinyin is a way of writing Chinese syllables using the Latin alphabet and is more or less based on the character’s pronunciation. Because there are many different characters with the same pronunciation, the IME will show a list of all possible characters, from which the right character must be selected pressing a key from 1 to 9. Smart IMEs can even convert a whole string of Latin characters into a sensible sentence using a dictionary of common word combinations (similar to T9). You know who has a big dictionary of word combinations in any language? Right: Google. That’s why they created their own IME.

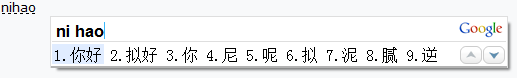

In this picture I typed “nihao”. Google’s IME shows the list of possible characters, with the most probable one first. Indeed, the characters meaning “you good” (the common greeting) are shown as the first option. The second option also represents “nihao” but has a different character for “ni” (I have no idea what that “ni” means). All other options only show characters for “ni”, and after selection the user would be presented with a new list with all options for “hao”. Also note the arrows pointing up/down: apparently there are more than 9 options for “nihao” so using Page Up and Page Down the user can cycle through all different characters.

This all sounds very complicated and tedious, but is very easy in practice. Just as with T9, it’s important that the IME has a good representative dictionary so its first guess is the right one. Many times it’s possible to type a complete Chinese sentence in pinyin without having to manually select any option from the list of characters. It gets tricky when the sentence contains non-Chinese words (for which you need to turn the IME off and back on) or proper names (for which the IME cannot guess the characters, although it will remember them for later.)

* yes, even though I’m Dutch and Dutch has its own keyboard layout, I don’t know anyone who uses it so for me the US keyboard layout is normal